Teaching guides developed in this project:

(click to open)

Teaching Guides

VR 360 Tool

How to use the tool:

Educative Principles

Overview

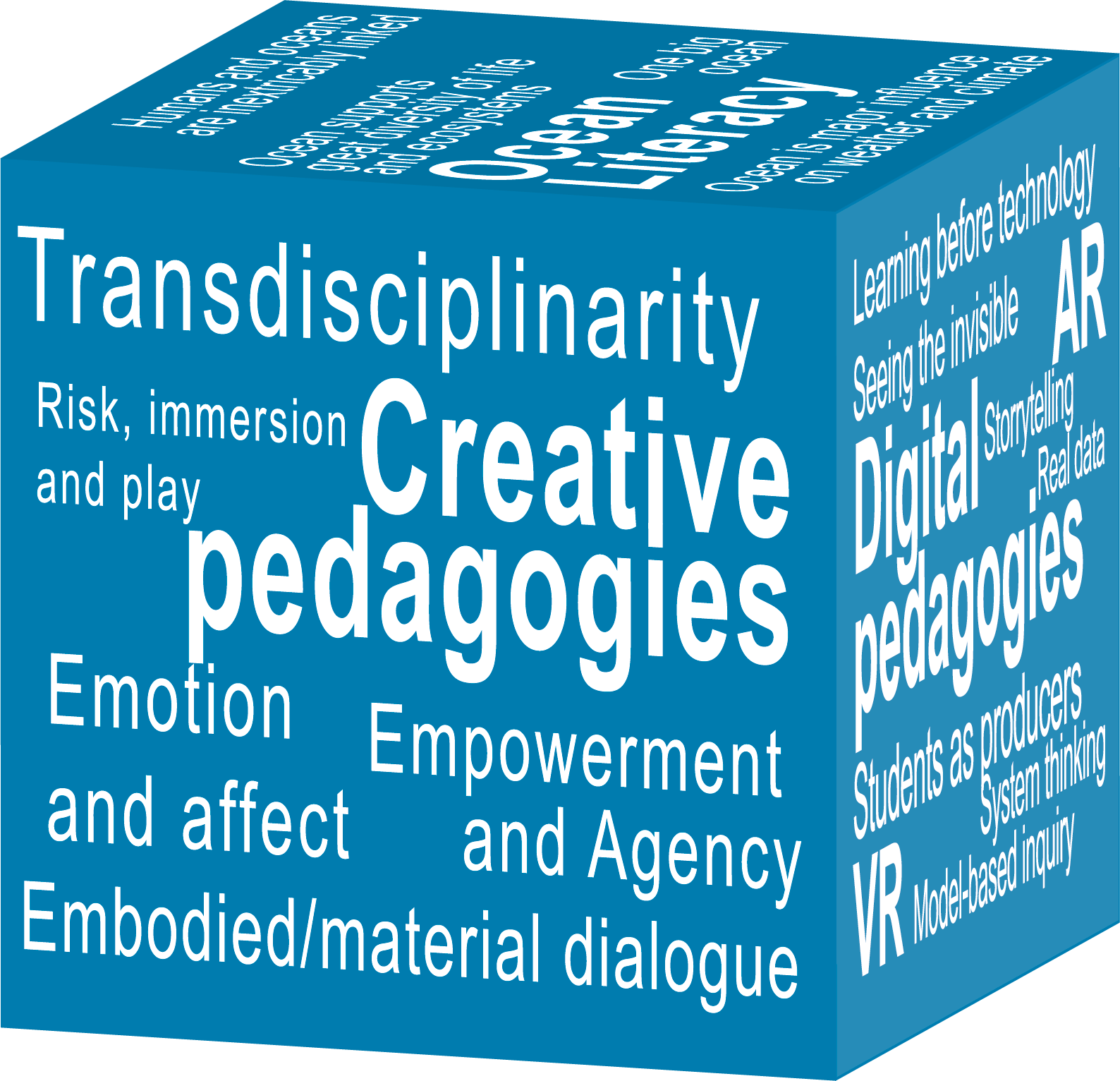

The overall aim of the Ocean Connections project is to explore pupils’ and teachers’ experiences of using a combination of creative pedagogies (teaching creatively and teaching for creativity) and digital technologies to help pupils connect with the Ocean and promote their Ocean Literacy. To do this, we drew on existing research into ocean literacy education, the use of creative pedagogies, and the use of digital technologies in teaching and learning to create a set of educative principles for use in designing teaching and learning experiences. We found no research that already synthesised these different elements. So we drew together a review of evidence into all three aspects of this project, searching for overlaps between them as well as identifying core themes in implementing ocean literacy education (also drawing on research into science in society), using digital tools, and using creative pedagogies. We have summarised these core themes for the different aspects of the project as faces on a cube (see image) to show them as parts of a whole.

Teachers can draw out connections between different ideas shown on the cube in their planning. For example, pupil empowerment and agency is a core principle in creative teaching and learning, and might be promoted through using digital tools that enable pupils to design their own virtual reality experience about the diversity of ocean life within the Oceans VR Tool rather than use a pre-existing VR experience – the ‘students as producers’ principle in using digital tools. Or pupils might use technology to access and analyse real data about the extent of ocean plastics alongside creating sculpture using recycled plastic from the Ocean to work in a transdisciplinary Science-Arts manner to learn about the inextricable relationship between humanity and the Ocean.

The importance of connection

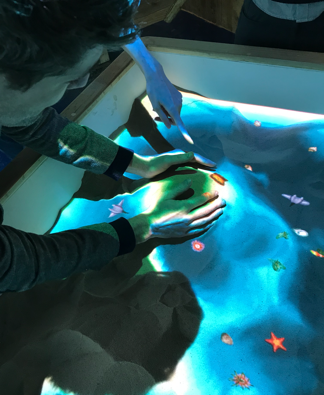

In order for pupils’ to be motivated to engage with developing their Ocean Literacy and to act on their learning to make positive change, it is important for them to be able to relate to and connect with the Ocean at an emotional, physical and an intellectual level. Both creative pedagogies and digital technologies can be used to achieve this (e.g. DuPont, 2017). In drawing on the evidence-based principles with respect to each of the aspects of this project, shown in the image as faces of a cube, teachers should look for ways of connecting creative and digital approaches and using them together to plan their teaching about the Ocean. For example, digital technologies such as virtual reality have the potential to make the inaccessible Ocean more accessible, but there is a balance to be struck with accessibility and placing a digital barrier between young people and their experience of nature. Creative pedagogies designed to promote empathy and felt, embodied knowledge can assist in breaking down any digital barrier whilst maintaining the digital affordance of greater accessibility.

Creative Pedagogies

An easy way to understand ‘creative pedagogies’ is to think about it in two ways. Firstly, it’s about how teachers use their own creativity to create engaging and effective learning experiences (teaching creatively) and secondly, it’s how those experiences facilitate students’ own creativity (teaching for creativity). Creative pedagogies is not a synonym for using the arts– this might be part of the process, but our previous research and literature review shows that in the context of Ocean Literacy there are eight key creative pedagogy features: empowerment and agency; individual, collaborative and communal activities for change; transdisciplinarity; dialogue; risk, immersion and play; possibilities; ethics and trusteeship; balance and navigation.

Encouraging Empowerment and Agency means that both learners and adult professionals gain a greater sense of their own ability to act, make a difference through problem-solving and express themselves, and to then know what to do with that in order to be more creative Ocean teachers/learners and to develop more creative Ocean teaching techniques.

Students also need space to engage individually, in collaborative relationships and in more communal or group-driven interactions, as they develop ideas which lead to change within the science/Ocean classrooms. Employing available tools such as technology (e.g. social media, VR) or arts processes to support this can build on what is possible creatively face to face. Research shows that teachers may need to put time into skilling students in this kind of group work in order to get the most from it.

Transdisicplinarity is grounded in the inter-relationship of different ways of thinking and knowing, which means allowing space for e.g. problem-solving, reasoning, exploring, around shared arts /science/ geography/ Oceans threads. It is about allowing curious questions to drive the learning with discipline knowledge and processes feeding into this, and is often recognizable in STEAM (Science, Technology, Engineering, Arts and Maths) practices.

Dialogue goes beyond the notion of verbal conversation to encompass a process of students’ questions leading to answers leading to questions; which can occur between people, disciplines, creativity, identity and ideas. This dialogue acknowledges embodiment (the fact that we all learn through an integrated bodymind (rather than just a disembodied mind) and allows for conflict and difference.

A trusting space is key for risk, immersion and play, for students to make mistakes without fear of failure. It often involves staff and students having fun, but also being brave and feeling a little uncomfortable. Play especially is closely related to imagination, going beyond the obvious, perhaps place-making around Oceans.

Creative pedagogy can allow for multiple possibilities both in terms of thinking and spaces, and knowing when it is appropriate to narrow or broaden these in the context of asking ‘what if…?’. This principle is derived directly from Craft’s Possibility Thinking theory which recommends achieving this particularly through the teacher stepping in and stepping back, as appropriate.

Ethics and Trusteeship means considering the impact of creative outcomes, and so, facilitating creativity in education wisely. Adult professionals and learners need to consider the ethics of their creative processes and products in relation to the Ocean, and should be guided in their decision-making by what matters to them as members of a wider Ocean-interested community. They can then be active as trustees of that decision-making and its outcomes.

The last creative pedagogy is Balance and Navigation and involves thinking about how balance control and freedom, structure and openness, and prior and new knowledge. The feature also includes acknowledging the common educational tensions and dilemmas of accountability/assessment, marketisation and resource/time pressures and navigating these with creativity rather than pursuing a creativity v performativity mentality.

Working with creative pedagogies may require a re-arrangement of traditional science-teaching power dynamics.

Links

- https://www.creativityexchange.org.uk/ideas-hub/the-powerful-impact-of-creativity-in-the-classroom

- https://sciartsedu.co.uk

Multimedia

Digital Technologies

An easy way to understand ‘creative pedagogies’ is to think about it in two ways. Firstly, it’s about how teachers use their own creativity to create engaging and effective learning experiences (teaching creatively) and secondly, it’s how those experiences facilitate students’ own creativity (teaching for creativity). Creative pedagogies is not a synonym for using the arts– this might be part of the process, but our previous research and literature review shows that in the context of Ocean Literacy there are eight key creative pedagogy features: empowerment and agency; individual, collaborative and communal activities for change; transdisciplinarity; dialogue; risk, immersion and play; possibilities; ethics and trusteeship; balance and navigation.

Encouraging Empowerment and Agency means that both learners and adult professionals gain a greater sense of their own ability to act, make a difference through problem-solving and express themselves, and to then know what to do with that in order to be more creative Ocean teachers/learners and to develop more creative Ocean teaching techniques.

Students also need space to engage individually, in collaborative relationships and in more communal or group-driven interactions, as they develop ideas which lead to change within the science/Ocean classrooms. Employing available tools such as technology (e.g. social media, VR) or arts processes to support this can build on what is possible creatively face to face. Research shows that teachers may need to put time into skilling students in this kind of group work in order to get the most from it.

Transdisicplinarity is grounded in the inter-relationship of different ways of thinking and knowing, which means allowing space for e.g. problem-solving, reasoning, exploring, around shared arts /science/ geography/ Oceans threads. It is about allowing curious questions to drive the learning with discipline knowledge and processes feeding into this, and is often recognizable in STEAM (Science, Technology, Engineering, Arts and Maths) practices.

Dialogue goes beyond the notion of verbal conversation to encompass a process of students’ questions leading to answers leading to questions; which can occur between people, disciplines, creativity, identity and ideas. This dialogue acknowledges embodiment (the fact that we all learn through an integrated bodymind (rather than just a disembodied mind) and allows for conflict and difference.

A trusting space is key for risk, immersion and play, for students to make mistakes without fear of failure. It often involves staff and students having fun, but also being brave and feeling a little uncomfortable. Play especially is closely related to imagination, going beyond the obvious, perhaps place-making around Oceans.

Creative pedagogy can allow for multiple possibilities both in terms of thinking and spaces, and knowing when it is appropriate to narrow or broaden these in the context of asking ‘what if…?’. This principle is derived directly from Craft’s Possibility Thinking theory which recommends achieving this particularly through the teacher stepping in and stepping back, as appropriate.

Ethics and Trusteeship means considering the impact of creative outcomes, and so, facilitating creativity in education wisely. Adult professionals and learners need to consider the ethics of their creative processes and products in relation to the Ocean, and should be guided in their decision-making by what matters to them as members of a wider Ocean-interested community. They can then be active as trustees of that decision-making and its outcomes.

The last creative pedagogy is Balance and Navigation and involves thinking about how balance control and freedom, structure and openness, and prior and new knowledge. The feature also includes acknowledging the common educational tensions and dilemmas of accountability/assessment, marketisation and resource/time pressures and navigating these with creativity rather than pursuing a creativity v performativity mentality.

Working with creative pedagogies may require a re-arrangement of traditional science-teaching power dynamics.

Links

- https://www.creativityexchange.org.uk/ideas-hub/the-powerful-impact-of-creativity-in-the-classroom

- https://sciartsedu.co.uk

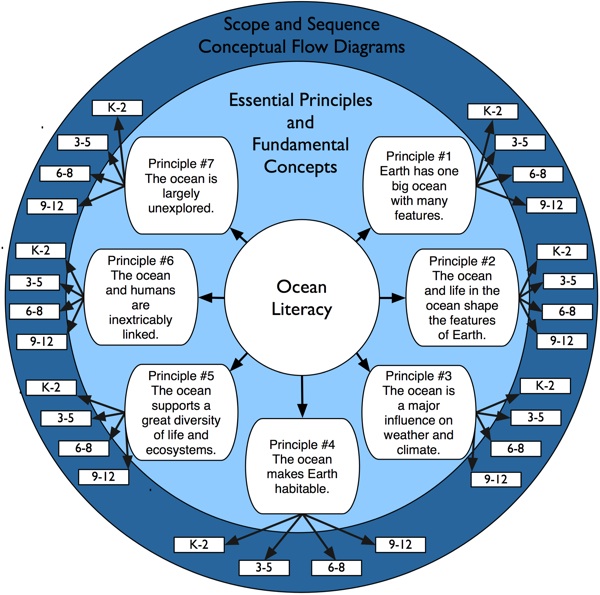

Ocean Literacy

The term “marine education”, which was in use until the turn of the century, has been replaced by the idea of “Ocean Literacy”. The latter term suggests a greater focus on the learner (which links to one of the key Creative Pedagogy themes: “empowerment and agency”.

A virtual conference in 2002 led to a consensus framework which identified learning outcomes for school-leavers:

- be aware of issues concerning the usage and sustainability of the oceans as a finite resource

- be cognisant of both global and local environmental issues and the interconnectedness of all species

- be knowledgeable of technological impacts on oceans

- be able to diagram ocean problems, policies, and issues

- be aware of the importance that oceans serve in our daily lives

- be knowledgeable of the enormity and complexity of oceans

These principles underpin much of the projects’ approach to ocean literacy. However, they have an overtly science-focused approach and we have broadened them out considerably.

One Big Ocean addresses a common misconception that there are many oceans. Dupont (2017) describes a project called “I am the Ocean” – an interdisciplinary activity developed by an artist and a scientist “to help students understand, connect and be equipped to take actions on marine global changes” (p. 1211).

Humans and the Ocean Inextricably Linked provides an opportunity to see that the ocean affects us and vice-versa. Teaching for ocean literacy, then, requires a willingness to engage with a range of disciplines including science, art, mathematics, history and geography. Effective practice would normally be expected to involve some practical activity such as engaging in recycling or a beach clean-up.

Ocean Diversity recognises that there the ocean contains a huge number of diverse species. Visits to aquaria and zoos provide opportunities to see real specimens to add value to the classroom learning.

Influence on Weather & Climate Links can be supported by a range of resources (for example, https://oceanservice.noaa.gov/education/literacy.html). Students can study long-term weather patterns and examine their impact on individuals and societies over time.

Science/Society Pedagogies: Inquiry offers an opportunity for students to carry out investigations to answer their own questions. Longer-term projects might involve monitoring levels of pollution. Such activities reflect Cudaback’s (2006) conceptualisation of ocean literacy: “an ocean-literate person understands ocean science, can communicate about the ocean, and is able to make informed decisions that affect the ocean” (p. 418).

Student questioning recognises that each learner has their own questions and that these can be used to trigger investigations and inquiries using first-hand and second-hand data

Modelling encourages students to use data to create better understandings of changes over time. Using models allows people to make predictions about future events and, if necessary, to mitigate against those impacts.

Place and Community encourages students to recognise that their sense of place will, in some way be influenced by the ocean whether through what they eat or in terms of the influence of trade on communities.

Multimedia

The Ocean Connections Principles for Creative, Digital Ocean Learning

Principle 1: The content sequence of the learning about Ocean Literacy in the Ocean Connections project will connect to one or more of the following principles of Ocean Literacy, as appropriate for the age of the pupils and their prior learning:

- Humans and the Ocean are inextricably linked

- The Ocean supports a great diversity of life and ecosystems

- There is one big Ocean

- The Ocean is a major influence on weather and climate

Principle 2: Teaching and learning with respect to Ocean Literacy in the Ocean Connections project will aim to bridge disciplinary boundaries by enabling pupils to use knowledge, ideas and processes from different disciplines in order to ask and answer their own questions.

Principle 3: Teaching and learning with respect to Ocean Literacy in the Ocean Connections project will draw on key features of creative pedagogies, such as playful and immersive experiences, to connect pupils with the ocean both intellectually and affectively. They will promote embodied and material dialogic interaction with the Ocean, nature and technology, and aim to empower pupils to work individually and collaboratively.

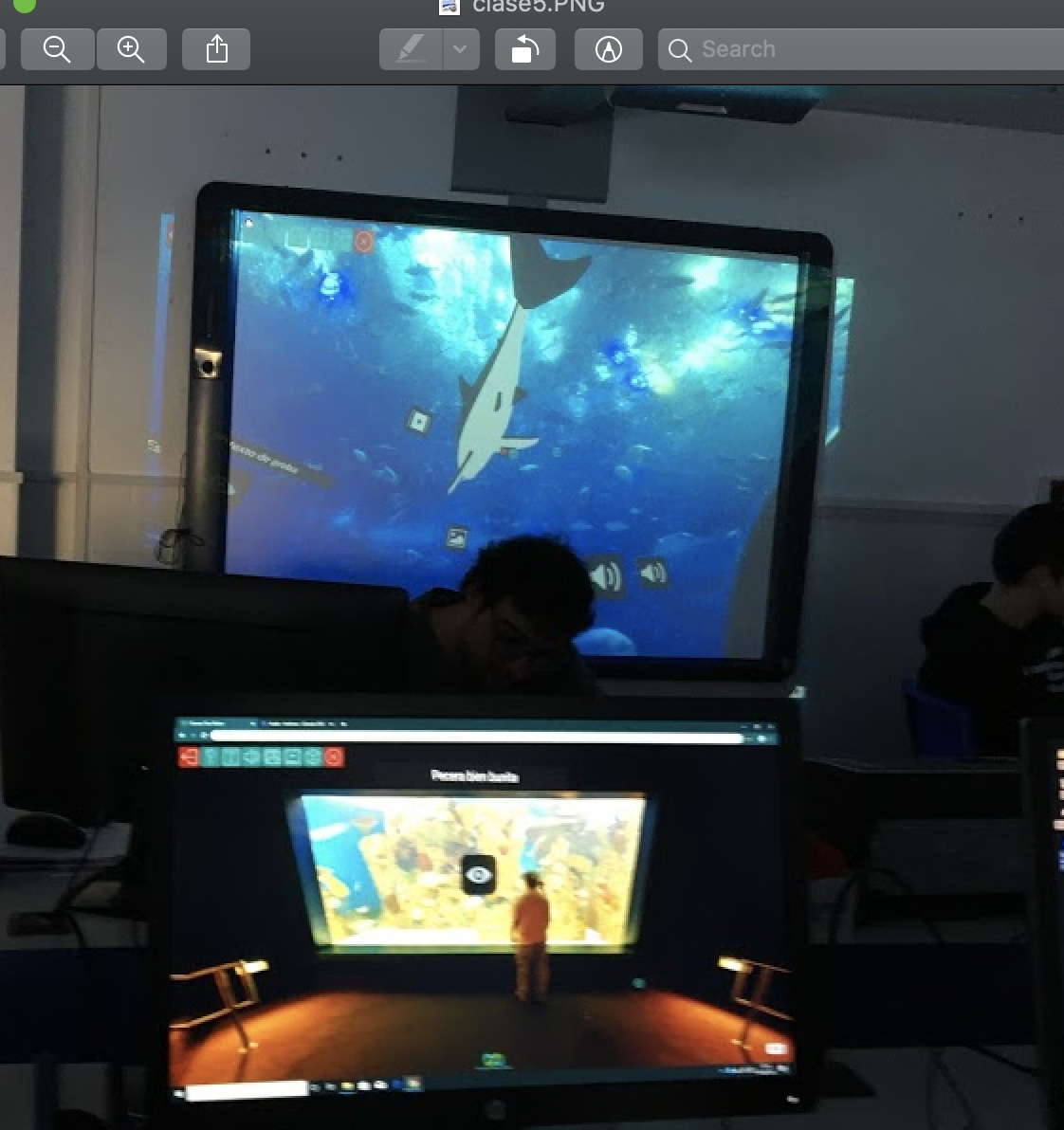

Principle 4: Digital technologies should be used to support model-based inquiry and data-driven learning as part of the ocean connections projects, using real-time data where possible. Pupils should have opportunity to design their own models and use them to explore their thinking.

Principle 5: Virtual and/or augmented reality technologies should be used to support pupil learning, enabling them to visualise otherwise difficult to access phenomena and processes, including systems approaches to critical concepts with respect to ocean learning.

Principle 6: Technologies can be used to support communication with external stakeholders such as scientists and the public, enabling pupils to learn about the ocean within a wider community context linked to the creative pedagogy feature individual, collaborative and communal action for change.